Pigs, Grizzlies, and a Surprising Skincare Secret

How veterinary research is changing what we know about aging skin

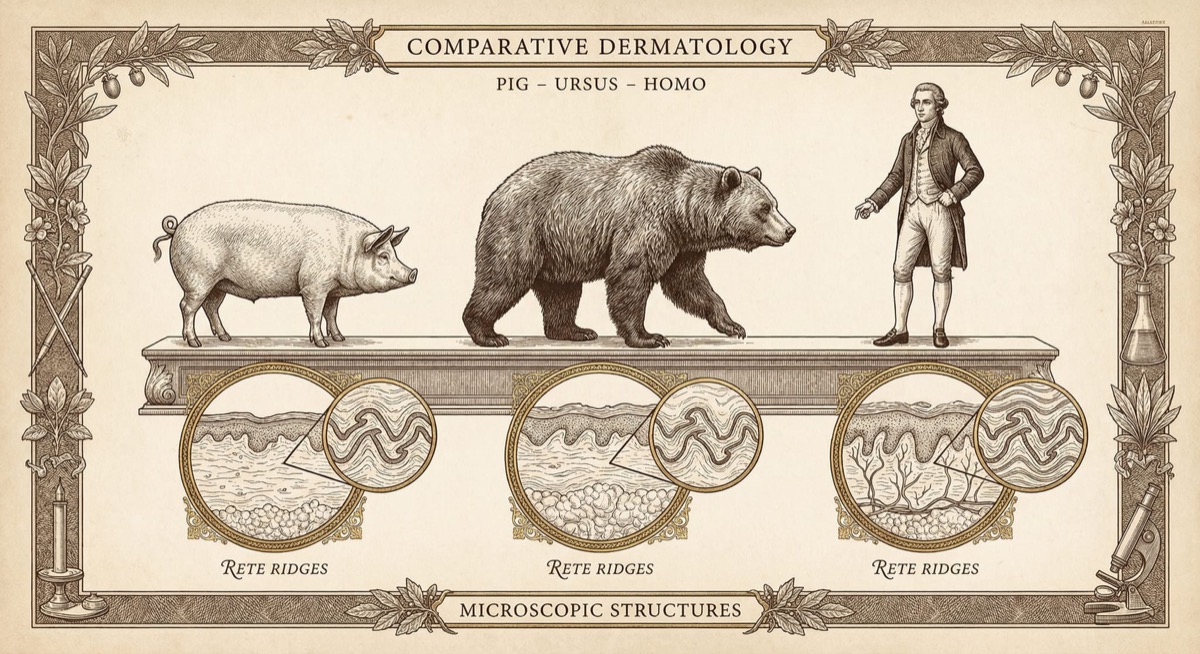

What do pigs, grizzly bears, and humans have in common? A microscopic skin feature that could revolutionize anti-aging treatments, and the discovery came from researchers at a veterinary college.

For decades, scientists assumed that rete ridges, the tiny valley-like structures that anchor our outer skin to the dermal layer beneath, formed during fetal development. That assumption was wrong, and it took veterinary researchers looking beyond the usual lab animals to figure it out.

The Discovery That Changed Everything

A groundbreaking study published this week in Nature by researchers at Washington State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine has upended our understanding of skin biology. The team, led by Associate Professor Ryan Driskell and doctoral student Sean Thompson, discovered that rete ridges actually form after birth, not before, and identified the molecular signal that drives their development.

This might sound like a minor technical detail, but the implications are enormous. Rete ridges act like biological Velcro, anchoring the epidermis to the dermis while maintaining skin elasticity and strength. As we age, these ridges flatten, leading to thinner, sagging skin that’s more prone to damage.

“These structures degrade as we age; now we know how they form and have a blueprint to guide future work on restoring them.” — Ryan Driskell, WSU College of Veterinary Medicine

Why Pigs and Bears, Not Monkeys?

Here’s where the story gets fascinating. For years, skin research hit a wall because scientists were studying the wrong animals. Mice and monkeys, the traditional biomedical research models, don’t have rete ridges. Their furry skin simply lacks these structures.

It wasn’t until the WSU team looked beneath the surface of various mammals that they discovered something remarkable: animals with thicker skin, like pigs, grizzly bears, and even dolphins, share these ridge structures with humans.

“When most people look at the skin of different animals, they see differences in fur. Rete ridges lie under the surface of skin, however, so it wasn’t until we looked closer that we discovered that animals with thicker skin, like pigs, grizzly bears and dolphins, have rete ridges like we do.” — Sean Thompson, PhD student

The grizzly bear provided crucial evolutionary data suggesting that body size dictates skin structure. But tracking day-by-day development in grizzlies? Not exactly practical. Enter the pig, an animal with a developmental timeline researchers could precisely monitor.

From Farm to Lab: The Pig Collaboration

Partnering with local farmers near Pullman, Washington, the WSU team collected skin tissue samples from pigs at various developmental stages. What they found surprised everyone: rete ridges form after birth, not during embryonic development.

“We expected this structure to be established before birth, so seeing it emerge afterward was a surprise. That timing changes how we think skin architecture is built and why it may be possible to influence it later in life.” — Ryan Driskell

Using advanced genetic mapping techniques, the team identified bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling as the key pathway that activates rete ridge formation. This discovery is particularly exciting because BMP proteins have already been FDA-approved for other applications, potentially smoothing the path for new skincare treatments.

Collaboration Across Institutions

The research exemplifies the collaborative nature of modern veterinary science. The study involved WSU’s Bear Research, Education and Conservation Center, partnerships with local agricultural producers, the University of Washington Birth Defects Research Laboratory, and clinical collaborators at Spokane Dermatology.

Maksim Plikus, a professor at UC Irvine and co-author on the paper, highlighted the translational potential: “Use of BMP proteins has already been FDA-approved for orthodontic applications, mapping the way for their use in aged skin and scars.”

What This Means for the Future

The implications extend far beyond cosmetic anti-aging treatments. Understanding how rete ridges form could lead to:

- Improved wound healing and scar repair — Reactivating BMP signaling might help restore normal skin architecture after injuries

- New treatments for skin conditions — Disorders like psoriasis could potentially benefit from therapies targeting these pathways

- Better livestock health — Understanding skin structure could help breed animals with traits suited to different climates

Driskell has already filed a provisional patent related to the discoveries.

A Win for Comparative Medicine

This research underscores why veterinary medicine matters to human health. Sometimes the answers we’re looking for aren’t in the obvious places. By studying pigs on a Washington farm and analyzing grizzly bear tissue, veterinary researchers solved a puzzle that had stymied the field for decades.

For veterinary professionals and graduates across the country, from Colorado State to UC Davis, Cornell to Texas A&M, Penn Vet to Purdue, this is a reminder that comparative medicine continues to yield discoveries that benefit both animals and humans alike.

The next time someone asks what veterinarians contribute to human medicine, you can tell them: maybe the secret to younger skin.

Study Reference

Thompson SM, Yaple VS, Searle GH, et al. Rete ridges form via evolutionarily distinct mechanisms in mammalian skin. Nature. 2026 Feb 4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-025-10055-5. PMID: 41639458.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the USDA Agricultural Research Service through the Resilient Livestock Initiative.